GLiCID

This page is one of the pages dedicated to beginners.

1. GNU/Linux Philosophy.

Unlike Windows systems, where file types are typically associated with specific applications via their extensions (e.g., .pdf,.docx,.exe), GNU/Linux and Unix-like systems follow a different philosophy: everything is a file, regardless of its extension.

In this environment, it is not the file extension that determines how a file is handled, but rather the user’s actions. It is up to the user to specify the appropriate program (via the correct command) or the relevant library path (via the PATH or LD_LIBRARY_PATH environment variables). This design provides significant flexibility and enables more granular control over file handling especially beneficial in systems intended for advanced or professional use.

However, in a shared environment, such as a multi-user server or cluster, users may face constraints regarding the choice and installation of software. These restrictions are intended to maintain system stability, security, and fair resource usage across all users. As a result, you will often need to adapt your workflows to the preinstalled tools or those provided via environment modules.

2. Filesystem Structure

This guide does not aim to detail the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS).

More advanced documentation will complement this guide later.

/

├── home/

│ └── userXXX/

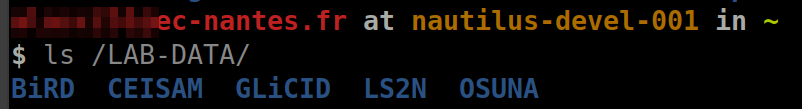

├── LAB-DATA/

│ ├── Entity1/

│ └── Entity2/

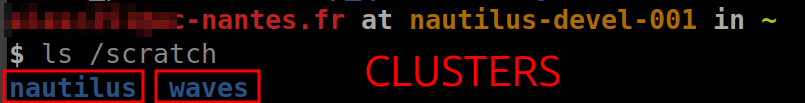

├── scratch/

│ ├── cluster1/

│ │ └── projectXXX/

│ └── cluster2/

│ └── userXXX/

└── opt/

├── modules/

└── software/

- /home/userXXX/

-

Description: Personal directory for each user.

This is where users store their personal files, scripts, and specific data. - /scratch/

-

Description: Temporary workspace used for intensive processing or intermediate files. Therefore, it is crucial to back up important results elsewhere.

- /LAB-DATA/

-

Description: Temporary space for ongoing calculations. Users submit their SLURM jobs from this directory. It is essential to back up important results elsewhere.

- /opt/

-

Description: Location where software and modules available to users are installed. With the module system, users can easily load or unload the necessary software environments for their tasks.

3. Basic Commands

Description: Running a command in Linux is generally structured as follows:

<command> -option [argument] (target)

Command chaining is done with the pipe |:

<command> -option [argument] (target) | <command> | etc.

Attention: The second command processes the output (result) of the previous command. This is different from &&:

<command> -option [argument] (target) && <command>

In this case, the second command executes only if the first one succeeds (return code 0).

To run the second command independently of the first, use &:

<command> -option [argument] (target) &

To redirect the output of a command to a file:

<command> > myfile.txt → Overwrites the file and writes into it.

<command> >> myfile.txt → Appends to the file without overwriting.

|

TIP: Autocompletion with the Tab key (to the left of the "a" key) will save you time:

<start_of_command\or\file>[TAB]<end_of_command\or\file> The |

4. Linux Survival Manual

# Check if you have a command and its location.

whereis <command>

# Show the manual for a command

man <my_command>

# Yes, you can even display the manual for "man" itself!

man man

# Know the current directory

pwd

# List items in the current directory

ls

# List all files, including hidden ones, with details

ls -la

# Create a file

touch <myfile.txt>

# Edit a file

nano or vim <myfile.txt>

Basic nano commands:

- CTRL + X: Exit.

- CTRL + O: Save.

- CTRL + K: Cut.

- CTRL + U: Paste.

VIM is a more powerful editor that requires more practice.

# View the contents of a file

cat <myfile.txt>

# Output is too large for the screen? Paginate the display:

cat <myfile.txt> | less

# Change directory

cd <path/to/directory>

# Move up one level

cd ..

# Copy a file

cp <source> <destination>

# Move or rename a file

mv <source> <destination>

# Remove a file (-r for a directory)

rm <myfile>

rm -r <mydirectory>|

WARNING: Deleting a file or directory does not require confirmation (Y/N) from the user, it is immediate and irreversible.

Make sure to make a backup of your file [ |

5. User Configuration Files

Linux systems allow each user to personalize their environment using configuration files stored in their home directory. These files are typically hidden (prefixed with a dot .) and are executed or read automatically by the shell or specific applications.

This file is executed every time a new interactive shell session is started (e.g., when opening a terminal).

Typical use cases:

- Setting environment variables

- Defining shell aliases

- Customizing the command prompt (PS1)

- Adding paths to $PATH

# Example: .bashrc

export EDITOR=vim

alias ll='ls -alF'

export PATH="$HOME/bin:$PATH"5.1. .bash_profile / .profile

These files are executed during login shells (e.g., when logging in via SSH). On some systems, .bash_profile may source .bashrc to ensure consistency.

# Example: .bash_profile

if [ -f ~/.bashrc ]; then

. ~/.bashrc

fi5.2. .ssh/config

This optional file allows you to define shortcuts and custom behavior for SSH connections.

# Example: ~/.ssh/config

Host myserver

HostName 192.168.1.10

User alice

Port 22

IdentityFile ~/.ssh/id_rsa_custom|

Make sure the permissions of your |

5.3. .gitconfig

This file stores your Git configuration, such as your username, email, aliases, and color preferences.

# Example: ~/.gitconfig

[user]

name = Alice Example

email = alice@example.com

[alias]

st = status

co = checkout|

TIP: |

5.4. Permission and User Management

$ ls -l file.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 user group 1234 April 7 12:34 file.txt

# In Linux, each file has three types of permissions:

- Read (r): Allows reading the file content.

- Write (w): Allows modifying the file.

- Execute (x): Allows executing a file (for scripts or programs).

- First three characters : Permissions for the file owner (U)

- Next three characters : Permissions for the group (G)

- Last three characters : Permissions for other users (O)

# Symbolic Mode

`chmod u+x file` : Adds execute permission for the owner (user).

`chmod go-w file` : Removes write permission for the group and others.

# Octal Mode

`chmod 755 file` +

*Owner:* read, write, execute (7 = 4+2+1)

*Group:* read and execute (5 = 4+1)

*Others:* read and execute (5 = 4+1)|

Best practice: If you are not comfortable with octal mode, prefer symbolic mode. |

# Voir les permissions d’un dossier (sans lister son contenu)

ls -ld <dossier>

# Appliquer des permissions de manière récursive (dossier et contenu)

chmod -R 755 <dossier>

# Donner tous les droits à l'utilisateur (à utiliser avec précaution)

chmod 700 <fichier>

# Retirer tous les droits pour les autres utilisateurs

chmod o-rwx <fichier>

# Change file permissions (e.g., make a script executable)

chmod +x <myscript.sh>

# Change file ownership

chown <user>:<group> <file>|

Astuce : |

# List connected users

who

w

# View a user's groups

groups <user>

# Créer un nouvel utilisateur

sudo adduser <nom_utilisateur>

# Supprimer un utilisateur et son répertoire personnel

sudo userdel -r <nom_utilisateur>

# Ajouter un utilisateur à un groupe

sudo usermod -aG <groupe> <utilisateur>

# Voir les groupes d’un utilisateur

groups <utilisateur>

# Afficher les informations sur l'utilisateur courant

id

# Créer un groupe

sudo groupadd <nom_du_groupe>

# Changer le groupe propriétaire d’un fichier

chgrp <groupe> <fichier>|

Sometimes, you may need to add a user to system groups (like Also, be careful with overly restrictive permissions such as Balance is key: restrict access when necessary, but always ensure the required functionality is preserved. |

5.5. Process and Performance Management

# View current processes

ps aux # Shows all processes with details

- a : Shows all processes.

- u : Shows processes with more details (user, CPU, memory).

- x : Shows all processes, even those without a terminal.

top # Displays real-time processes

htop # Enhanced version of "top", if installed

# Kill a process (replace <PID> with the process number)

kill <PID>

kill -9 <PID> # Force close

pkill <process_name> # Kill a process by name6. File Search and Manipulation

# Search for a file in a directory (requires permissions on the target directory).

find /TargetDirectory -name "myfile.txt" 2>/dev/null

# Search for text in a file

grep "keyword" myfile.txt

# Find all files containing "error" in the current folder

grep -r "error" .

# View file and directory sizes

du -sh * # File/folder sizes in the current directory

# Check available disk space

df -h7. Compression and Archiving

# Create a tar archive

tar -cvf myarchive.tar folder/

# Compress an archive with gzip

tar -czvf myarchive.tar.gz folder/

# Extract a tar.gz archive

tar -xzvf myarchive.tar.gz

- c : Create an archive.

- v : Show files added to the archive.

- f : Specify the name of the archive to create.8. File Transfer over Network (scp, rsync, etc.)

# Copy a file to a remote server

scp file.txt user@server:/path/destination/

# Copy a folder to a remote server (with -r)

scp -r folder/ user@server:/path/destination/

# Copy a file from a remote server

scp user@server:/path/file.txt ./destination/

# Change the SSH port if needed (e.g., port 2222)

scp -P 2222 file.txt user@server:/path/9. Download and Synchronization: rsync, wget, and curl

# Synchronize a local folder with a remote folder

rsync -avz /localfolder/ user@remote:/remotefolder/

# Download a file from the internet

wget https://example.com/myfile.txt

# Download a file with curl

curl -O https://example.com/myfile.txt10. Conclusion

Operating within a shared Linux environment with limited privileges may initially seem restrictive. However, a solid understanding of foundational concepts and the appropriate use of available tools enable users to work independently and efficiently.

Through consistent practice, you will develop natural proficiency and confidence in the shell environment. Consulting manual pages, engaging in structured experimentation, and studying practical use cases are essential strategies for advancing your expertise even in highly constrained settings.